The White Rose Society

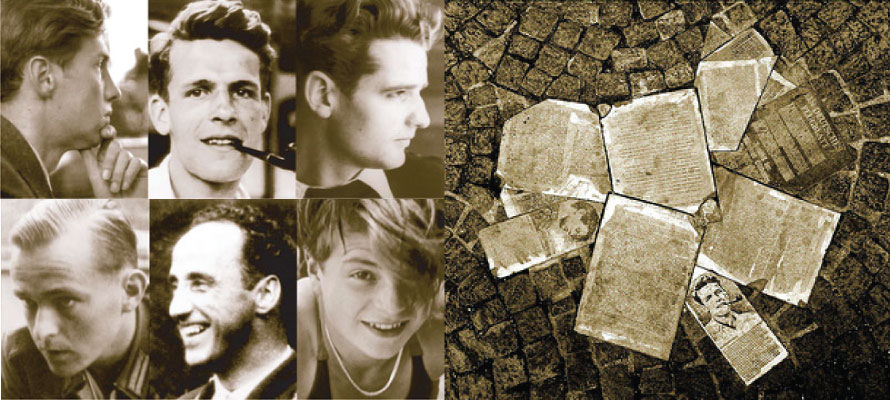

In the early summer of 1942, a group of young people — including Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, Alex Schmorell, and Hans and his sister Sophie Scholl (all in their early twenties), as well as their professor of philosophy, Kurt Huber, formed a non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943 that called for active opposition to the Nazi regime.

The group co-authored six anti-Nazi Third Reich political resistance leaflets. Calling themselves The White Rose, they instructed Germans to passively resist the Nazis. They had been horrified by the behavior of the Germans on the Eastern Front where they had witnessed a group of naked Jews being shot in a pit. The White Rose was influenced by the German Youth Movement, of which Christoph Probst was a member. Hans Scholl was a member of the Hitler Youth until 1936 and Sophie was a member of the Bund Deutscher Mädel.

Between June 1942 and February 1943, they prepared and distributed six different leaflets, in which they called for the active opposition of the German people to Nazi oppression and tyranny. Huber drafted the final two leaflets. A draft of a seventh leaflet, written by Christoph Probst, was found in the possession of Hans Scholl at the time of his arrest by the Gestapo, who destroyed it. Alex Schmorell and Hans Scholl wrote four leaflets, copied them on a typewriter with as many copies as could be made, probably not exceeding 100, and distributed them throughout Germany. These leaflets were left in telephone books in public phone booths and mailed to professors and students. They also were taken by courier to other universities for distribution. Additionally, some recipients were chosen from telephone directories and were generally scholars, medics and pub-owners in order to confuse the Gestapo investigators. All four were written in a relatively brief period, between June 27 and July 12.

The members of The White Rose worked day and night, cranking a hand-operated duplicating machine thousands of times to create the leaflets which were each stuffed into envelopes, stamped and mailed from various major cities in Southern Germany. Producing and distributing such leaflets sounds simple from today’s perspective, but, in reality, it was not only very difficult but even dangerous. Paper was scarce, as were envelopes. And if one bought them in large quantities, or for that matter, more than just a few postage stamps (in any larger numbers), one would (have) become instantly suspect.

In “Passive Resistance to National Socialism,” published in 1943 the group explained the reasons why they had formed the White Rose group:

“We want to try and show them that everyone is in a position to contribute to the overthrow of the system. It can be done only by the cooperation of many convinced, energetic people — people who are agreed as to the means they must use. We have no great number of choices as to the means. The meaning and goal of passive resistance is to topple National Socialism, and in this struggle we must not recoil from our course, any action, whatever its nature. A victory of fascist Germany in this war would have immeasurable, frightful consequences.”

The White Rose group also began painting anti-Nazi slogans on the sides of houses. This included “Down With Hitler,” “Hitler Mass Murderer” and “Freedom.” They also painted crossed-out swastikas.

The group expanded into an organization of students in Hamburg, Freiburg, Berlin, and Vienna. At great risk, “White Rose” members advocated the sabotage of the armaments industry. “We will not be silent,” they wrote to their fellow students. “We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!” Because the students were aware that only military force could end Nazi domination, they limited their aims to achieve “a renewal from within of the severely wounded German spirit.”

On 18 February 1943, coincidentally the same day that Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels called on the German people to embrace total war in his Sportpalast speech, the Scholls brought a suitcase full of leaflets to the university. They hurriedly dropped stacks of copies in the empty corridors for students to find when they flooded out of lecture rooms. Leaving before the class break, the Scholls noticed that some copies remained in the suitcase and decided it would be a pity not to distribute them. They returned to the atrium and climbed the staircase to the top floor, and Sophie flung the last remaining leaflets into the air. This spontaneous action was observed by the custodian Jakob Schmid. The police were called and Hans and Sophie Scholl were taken into Gestapo custody. Sophie and Hans were interrogated by Gestapo interrogator Robert Mohr, who initially thought Sophie was innocent. However, after Hans confessed, Sophie assumed full responsibility in an attempt to protect other members of the White Rose. Despite this, the other active members were soon arrested, and the group and everyone associated with them were brought in for interrogation.

“Be Strong in Spirit and Tender in Heart.” —Hans to his sister Sophie as they headed into the courtroom.

Sophie and Hans were questioned for four days in Munich, and their trial was set for 22nd February. They, along with Christoph (age 25), were arrested. Within days, all three were brought before the People’s Court in Berlin. On February 22, 1943. The trial was run by Roland Freisler, head judge of the court, and lasted only a few hours, they were convicted of treason and sentenced to death. All three were noted for the courage with which they faced their deaths, particularly Sophie, who remained firm despite intense interrogation. She said to Freisler during the trial, “You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly that you won’t admit it?” Only hours later, the court carried out that sentence by guillotine. All three faced their deaths bravely. Prison officials, in later describing the scene, emphasized the courage with which Sophie (age 21) walked to her execution. Her last words were: “How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause. Such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go, but what does my death matter, if through us, thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?” and in his final moments, Hans (age 25) cried out his last words, “Long Live Freedom!”

Alexander Schmorell (age 25) and Kurt Huber (age 49) were beheaded on 13 July 1943, and Willi Graf (age 25) on 12 October 1943. Huber’s widow was sent a bill for 600 marks (twice her husband’s monthly salary) for “wear of the guillotine.” Friends and colleagues of the White Rose, who had helped in the preparation and distribution of leaflets and in collecting money for the widow and young children of Probst, were sentenced to prison terms ranging from six months to ten years.

The White Rose had the last word. Their last leaflet was smuggled by Helmuth James Graf von Moltke out of Germany through Scandinavia to the United Kingdom, and in July, 1943, Allied planes air-dropped millions of copies over Germany, retitled “The Manifesto of the Students of Munich.”

“It’s high time that Christians made up their minds to do something . . . What are we going to show in the way of resistance – as compared to the Communists, for instance – when all this terror is over? We will be standing empty-handed. We will have no answer when we are asked: What did you do about it?” —Hans Scholl

Today, the members of the White Rose are considered in Germany to be amongst its greatest heroes, since they opposed the Third Reich in the face of almost certain death.

Taken in part from:

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The Holocaust.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005143. Accessed on June 5, 2014.

http://the-history-notes.blogspot.com/2011/05/white-rose-silenced-voices-of-hitlers.html